Treatment Research & Outcomes

This information is provided for reference only. The content is not intended to advertise specific outcomes or create unreasonable expectations. Therapeutic decisions should be made in consultation with a registered health practitioner.

For more lay-friendly information (e.g., easy reads, videos), see our RESOURCES page and posts from the RESOURCES section of our Blog.

Well-established empirically-supported treatments (EST) for paediatric feeding and behaviour/skills with 50 years of research support

See EST criteria reviews for feeding by Kerwin, 1999 & Volkert & Piazza, 2012 and for pica (a self-injurious behaviour/SIB) by Hagopian, Rooker, & Rolider, 2011. See review article by S.A. Taylor & T. Taylor, 2021 reviewed by the Association for Science in Autism Treatment (ASAT) https://asatonline.org/research-treatment/research-synopses/treatment-for-pediatric-feeding-problems/; & review article by T. Taylor & S.A. Taylor, 2023). See Hagopian et al., 2015 for a detailed summary and references on behavioural therapies and skill-teaching.

Our Outcomes Publications

(Taylor, Blampied, & Roglic’ 2020 n=26; Taylor & Taylor 2022 n=32) *Individual results may vary

*Note: This content is not intended to advertise specific outcomes or create unreasonable expectations. Each child and family are unique and the programme is individualised. Outcomes experienced by one person do not necessarily reflect the processes and results that other people may experience or guarantee the same outcomes. Outcomes may vary based on individual circumstances.

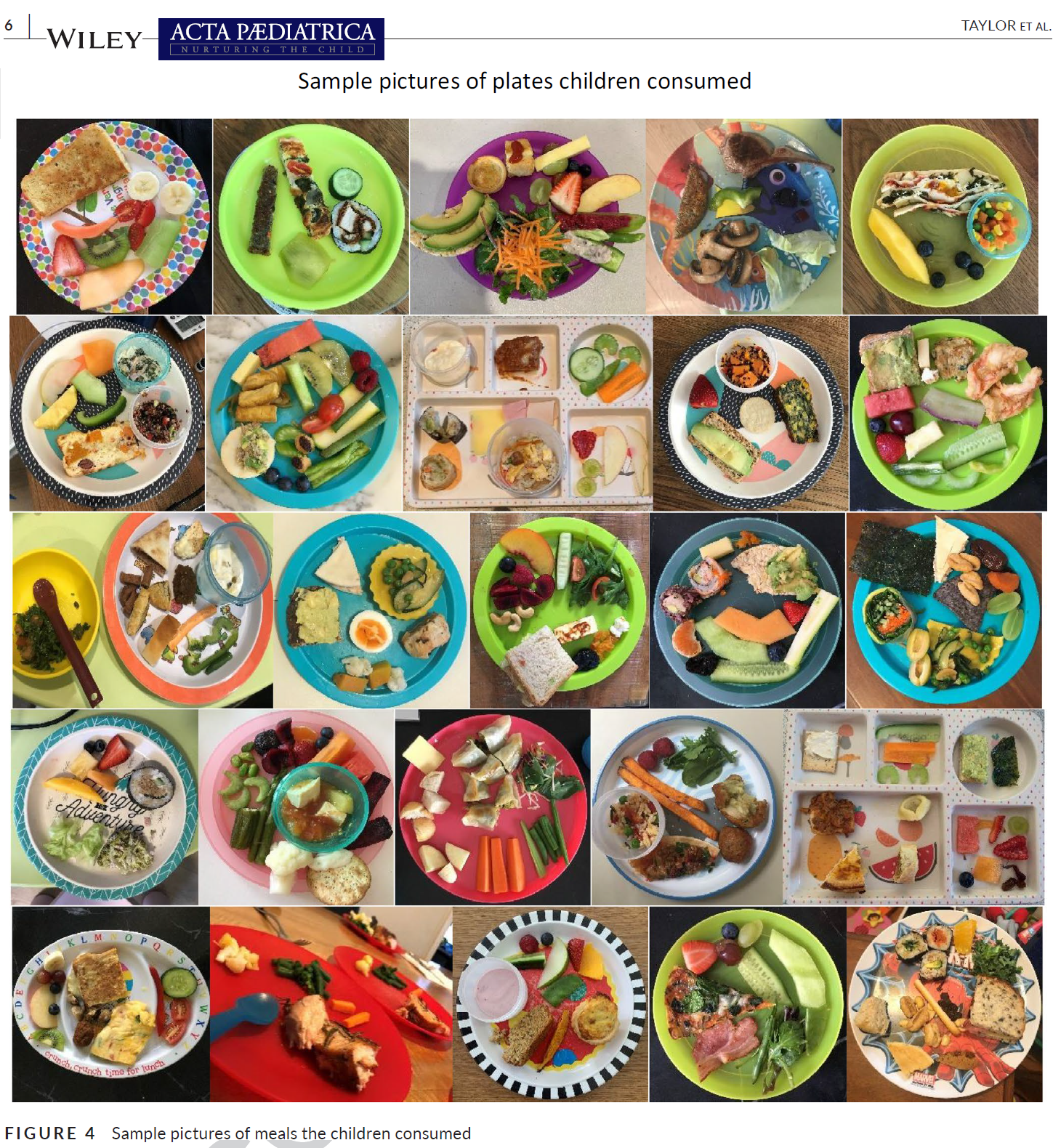

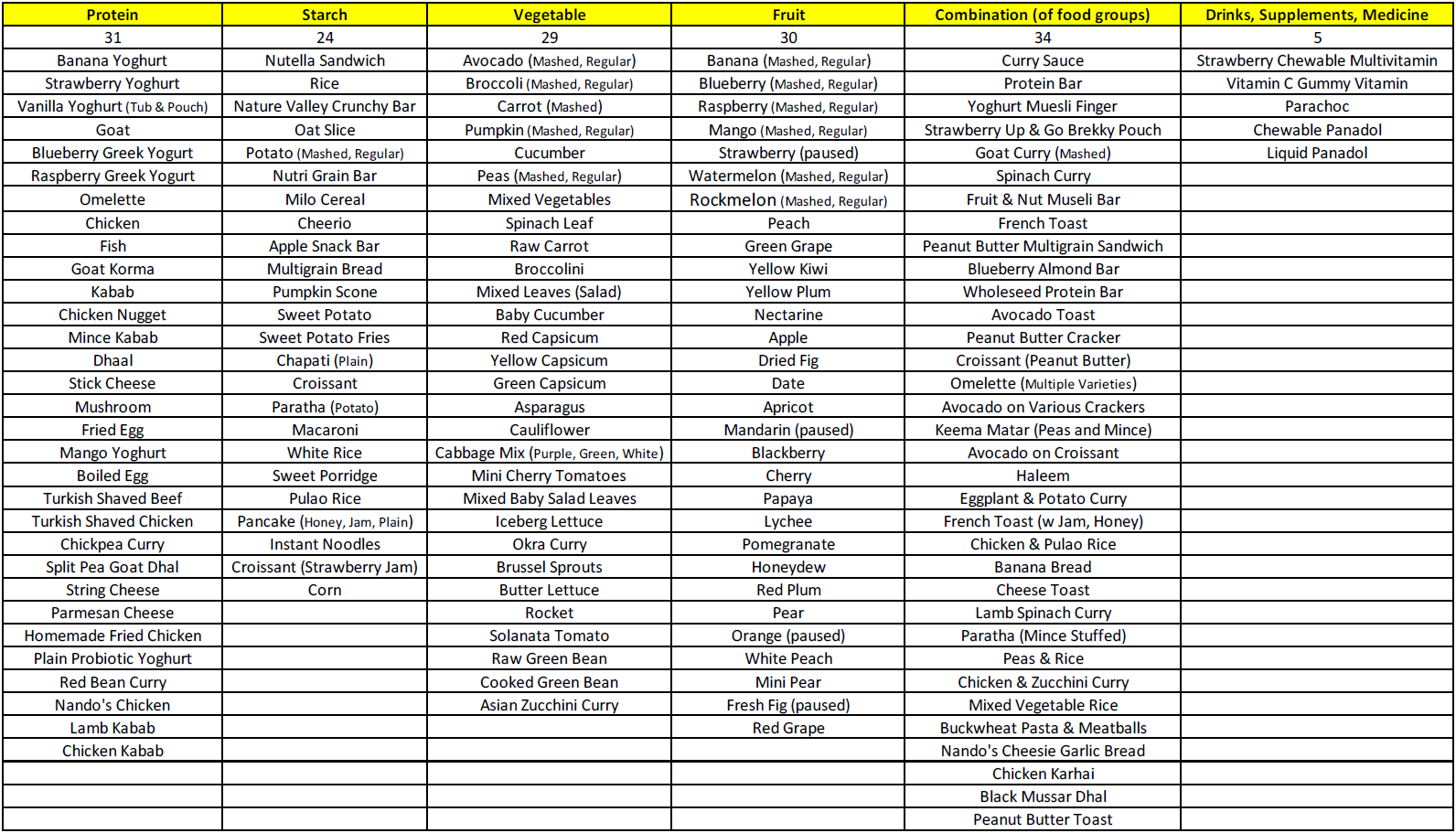

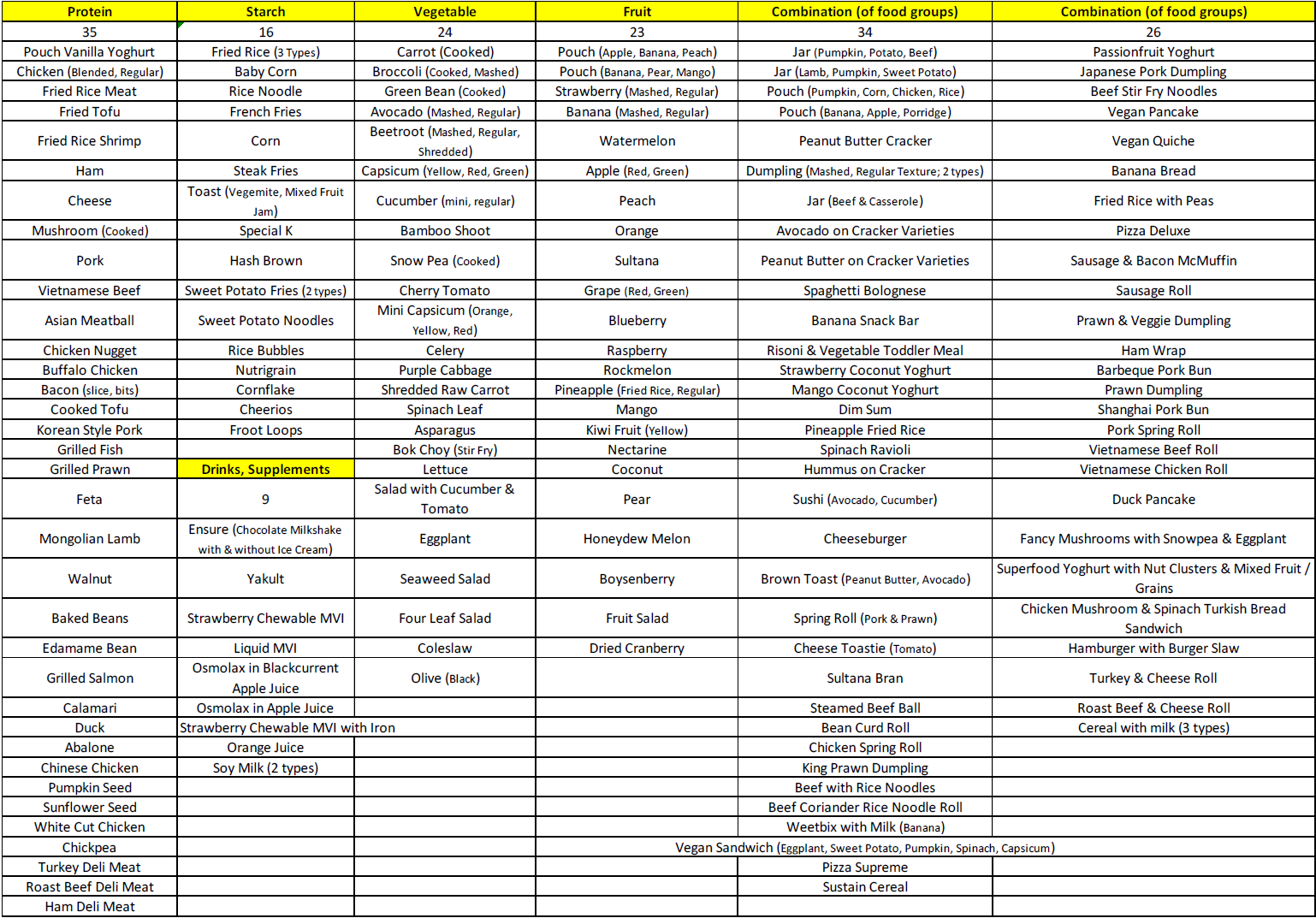

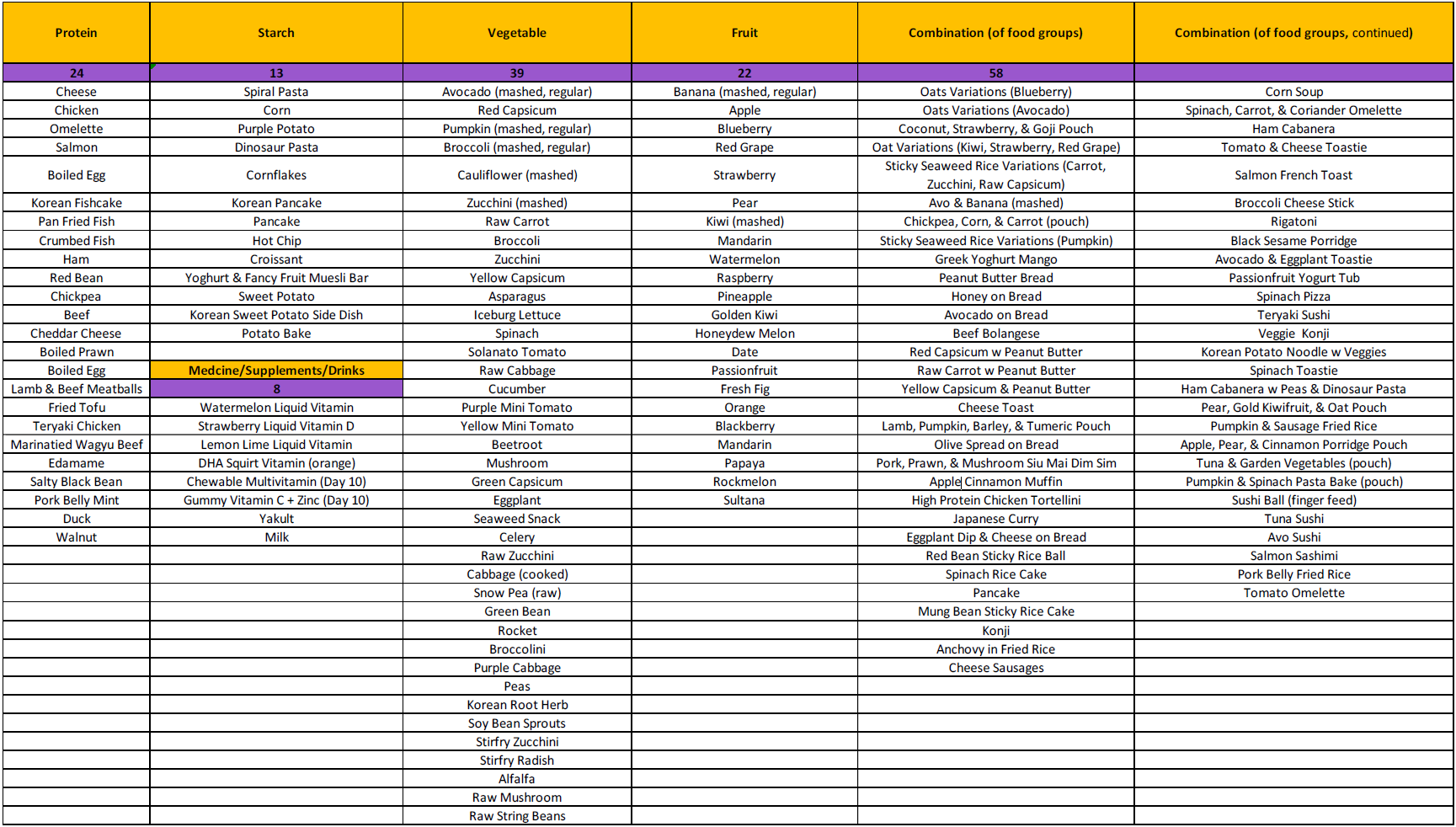

For Figure 4 (meal picture collage below), please see Taylor, Blampied, & Roglic’ 2020 n=26 for participant characteristics of the 26 patients over 2.8 years these meal pictures were compiled from, volume data on grams of consumption from these plates (before and after each session, plates were photographed both full and empty, and pre- and post- weights in grams were taking on a digital scale to ensure 100% consumption), realtime direct observational data on percentage consumption per session (via clean mouth checks), session duration in minutes, and admission length in days and hours per day. Consumption was confirmed in 3 ways: pre- post- photos, pre- post- grams, and realtime direct observational data taken on a specialised data collection programme on a laptop on percentage of consumption via mouth clean checks during the session. The timeframe was confirmed in 2 ways: session duration in minutes (realtime direct observational laptop data) and admission length in days and hours per day. We also compiled data on time to effect (achieving 100% consumption) in minutes. Operational definitions for outcome measures with reliability data (all meals were videotaped) and procedural fidelity/integrity data are provided in the publications, and more extensive details are provided in the method and results sections of the publications and supplemental files. These outcome data are summarised immediately below Figure 4.

Published Peer-Reviewed Consecutive Controlled Case Series (CCCS) Outcome Data Results

( Taylor, Blampied, & Roglic’ 2020 n=26 ; Taylor & Taylor 2022 n=32 )*

On average, children meet 100% of their individualised admission goals.*

Children consumed 100% of bites within an average of 46 minutes on the first day of treatment.

Children graduated in an average of 11 days.

Children learned to take medication, chew, feed themselves with utensils, drink water from a cup, and sit for meals without distractions.

Volume increased to an average of 158 grams.

Variety increased to >100 foods across all food groups (protein, starch, vegetable, fruit).

Dependence on supplements, formulas, and laxatives decreased.

Refusal/inappropriate mealtime behavior, spitting out, crying, and delays to taking bites/drinks significantly decreased by >97%.

Children swallowed bites/drinks faster (<30 seconds on average; i.e., packing decreased).

Gains maintained at an average of 2-year-follow-up (rated 4.24 out of 5).

*See

Hagopian (2020)

on the CCCS experimental design methodology.

*Note: Not a guaranteed result for all. Individual results may vary. This content is not intended to advertise specific outcomes or create unreasonable expectations. Each child and family are unique and the programme is individualised. Outcomes experienced by one person do not necessarily reflect the processes and results that other people may experience or guarantee the same outcomes. Outcomes may vary based on individual circumstances.

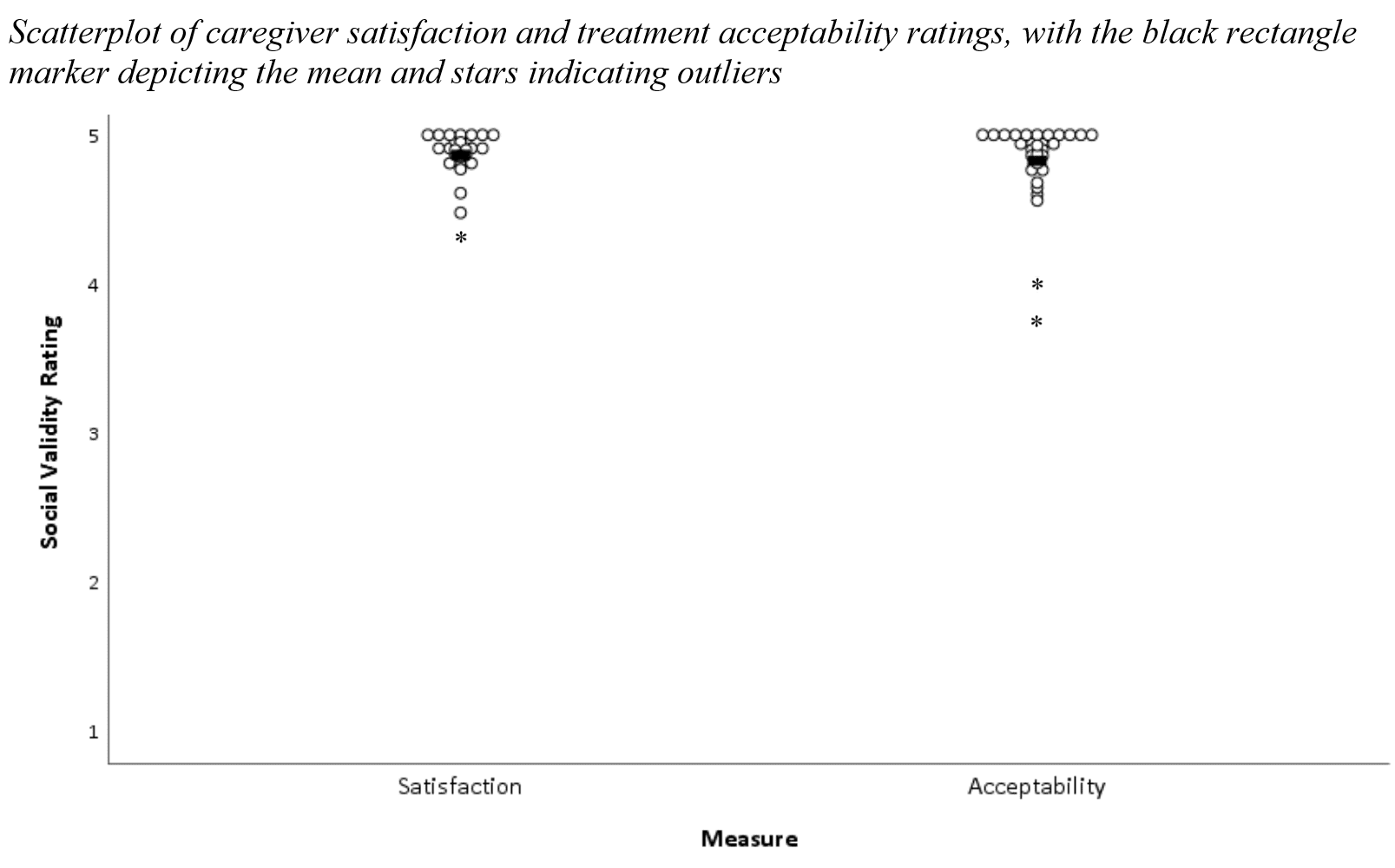

Social Validity

.

In addition to controlled data (e.g., % consumed, latency to acceptance, rates of inappropriate mealtime behaviour), permanent products (e.g., grams, meal photos), and objective measures (e.g., direct observation of child indices of happiness) for social validity, we have started asking caregivers for their perspectives and open-ended lived experiences (which in contrast is qualitative and subjective), and incorporated caregivers into scale development processes to create caregiver-informed measures.

Published peer-reviewed controlled studies

(

Taylor & Taylor, 2022 n=32

;

Taylor, Phipps, Peterson, & Taylor, 2024 (Systematic Review of 26 studies, n=409)

),

involving 3 other colleagues from 4 different sites across 3 countries,

have shown that successful behavioural feeding treatment can*:

Reduce caregiver stress.

Improve child emotional/behavioural functioning (internalising [emotional reactivity, anxiety, depressed mood, somatic complaints, withdrawal] and externalizing [aggression, attention problems] behaviour problems).

Increase child happiness.

Not negatively impact the quality of the mother-child relationship/attachment.

Caregivers report rippling positive impacts extending beyond eating for the child and family not only in health, but independence and social/behavioural areas.

With no negative side effects in follow-up.

*Note: Not a guaranteed result for all. Individual results may vary. This content is not intended to advertise specific outcomes or create unreasonable expectations. Each child and family are unique and the programme is individualised. Outcomes experienced by one person do not necessarily reflect the processes and results that other people may experience or guarantee the same outcomes. Outcomes may vary based on individual circumstances.

- On average, caregivers report high satisfaction with the programme (4.87 out of 5) and high social acceptability of the treatment (4.83 out of 5). Taylor & Taylor, 2022

Increase in Foods Consumed (Variety)

On average, children went from eating 6 to 94 foods across all food groups.

Previous Failed Treatments (Taylor & Taylor, 2021; Taylor, Blampied, & Roglic’, 2020)

Children had previously received up to 11 years of prior failed interventions by up to 12 different disciplines/treatment types (sensory/play, speech, physician (developmental paediatrician, GI, ENT, etc.), OT, dietitian, interdisciplinary feeding hospitals, hunger provocation/starvation, behavioural, medications (appetite, psychiatric, etc.), psychology/eating disorders, other (chiro, telehealth, equipment, hypnosis, research study), special diet).

Our Case Treatment Publications (with citation links)

- *Note: This content is not intended to advertise specific outcomes or create unreasonable expectations. Each child and family are unique and the programme is individualised. Outcomes experienced by one person do not necessarily reflect the processes and results that other people may experience or guarantee the same outcomes. Outcomes may vary based on individual circumstances.

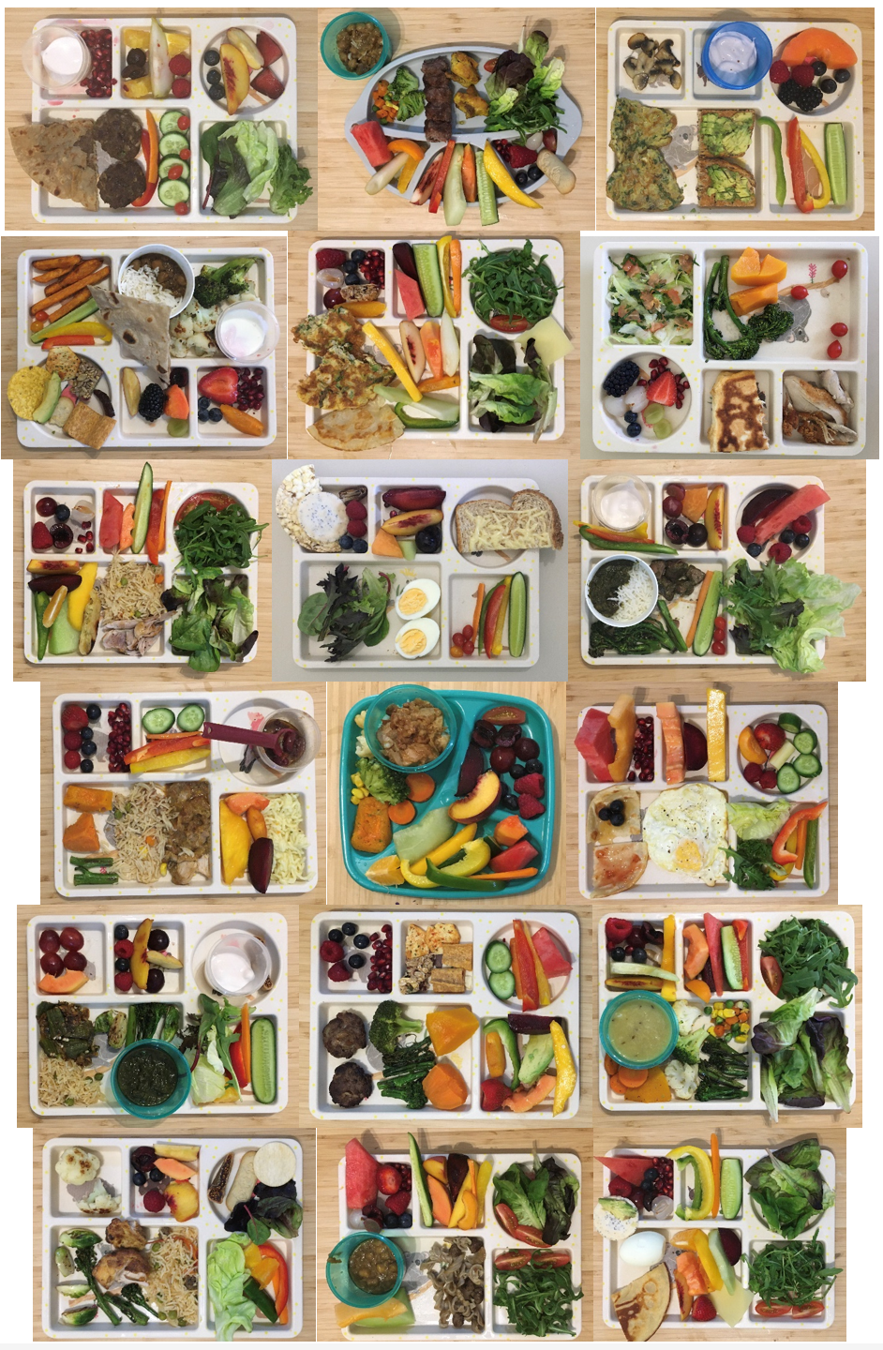

- For the meal photo collages below, please see the summaries and individual articles for further details on participant characteristics (each meal collage is one participant), volume data on grams of consumption from these plates (before and after each session, plates were photographed both full and empty, and pre- and post- weights in grams were taking on a digital scale to ensure 100% consumption), realtime direct observational data on percentage consumption per session (via clean mouth checks), session duration in minutes, and admission length in days and hours per day. Consumption was confirmed in 3 ways: pre- post- photos, pre- post- grams, and realtime direct observational data taken on a specialised data collection programme on a laptop on percentage of consumption via clean mouth checks during the session. The timeframe was confirmed in 2 ways: session duration in minutes (realtime direct observational laptop data) and admission length in days and hours per day. We also compiled data on time to effect (achieving 100% consumption) in minutes. Operational definitions for outcome measures with reliability data (all meals were videotaped) and procedural fidelity/integrity data are provided in the publications, and more extensive details are provided in the method and results sections of the publications and supplemental files.

These are only published cases from Australia and only selected feeding relevant diagnoses and conditions are listed for each case. The focus is on the specific individualised feeding needs/goals rather than diagnosis. In the hospital at Johns Hopkins/Kennedy Krieger, many diverse, severe, and complex feeding cases and issues were supported (Taylor, Kozlowski, & Girolami, 2017). In Australia, cases have had autism, developmental delay, intellectual disability, chromosomal abnormalities, coeliac disease, William’s syndrome, prematurity, constipation, anemia, nasogastric and gastrostomy tubes, failure to thrive, reflux, and dyspraxia, as well as typical development and no diagnoses at all.

Medication administration can be a significant issue in pediatric populations, and especially with patients with developmental disabilities and comorbid feeding disorders. Research has focused largely on consumption of solids rather than medication and liquids in pediatric feeding programs, with most studies being conducted within specialized hospital settings in the United States. No studies to our knowledge have detailed treatment evaluations for medication administration in pediatric feeding except for a few studies on pill swallowing. We report results of treatment protocols for medication administration using empirically-supported treatments in a short-term intensive home-based behavior-analytic program in Australia. Two males with autism spectrum (level 3) and pediatric feeding disorders participated in a 3-4 week program. We used a multiple baseline single-case experimental design for medication administration conducted concurrently with a treatment evaluation for solid foods. Consumption increased in number (9; supplements, laxatives, pain relievers), flavors (8; chocolate, blackcurrent and apple, strawberry, lemon-lime, orange, chocolate-vanilla, cherry, apple), forms (4; thin and thick liquids, chewables, gummies), and delivery methods (5; finger-fed, spoon, cup, medicine spoon, medicine cup) within the first treatment session. For one participant, we taught open cup drinking for a variety of liquids (milk, juices, medications). For both participants, we taught self-feeding with utensils for thick liquid medications. Treatment results were similar for solids and participants increased food variety to over 160 across food groups. All goals were met including training parents to maintain gains at home.

Mealtime Skill Independence: From Pouch-to-Spoon Fading to Using Chopsticks (Taylor, 2024)

Compared to solids, less paediatric feeding research has targeted liquids, medication, and teaching independence skills (e.g., fork, chopsticks). No research to our knowledge has reported transitioning from spout squeeze ‘baby food’ pouches, increasing finger-feeding, and teaching steps in scooping, sipping, and biting off portions. We detail a clinical case and depict data teaching comprehensive mealtime independence using multi-element and multiple-baseline designs. A 3-year-old male with paediatric feeding disorder, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), and autism spectrum disorder (level 3) had only one independent skill (yogurt pouch via spout). He did not finger-feed, self-spoon-feed, self-drink, or cup-drink. He participated in a home-based intensive 2-week behaviour-analytic treatment programme. We conducted an assessment comparing novel pouch transition apparatuses, then used pouch-to-spoon fading to teach spoon self-feeding. We taught independence in finger-feeding, open-cup drinking, and four methods of medication administration, then open-cup bolus sipping, self-scooping, biting off portions, fork, and chopsticks (11 skills). He met 100% of goals. Caregivers reported high social validity and relevant culturally significant information, and gains generalised and maintained in follow-up.

Pica is one of the most lethal self-injurious topographies. Despite this, more research is needed on teaching comprehensive adaptive skills to replace pica in varying contexts, particularly outside of specialised hospital admissions in the United States. Pica may include items such as sand, lotion, non-potable water, and clothing. Culturally, most Australians live near the coast. Australia has the highest skin cancer rates in the world, and for children enforces substantial mandatory sun protection and water safety measures (e.g., rash guard “rashie” tops, sun hats with school uniforms, sunblock, Surf Life Saving training). We present a case history of an 8.5-year-old male with pica and food stealing. He engaged in pica with his rashie, sun hats, and sunblock, and consumed substantial volumes of sand, sea water, seaweed, and chlorine swimming pool water. Behaviour-analytic assessment and treatment using single-case experimental designs occurred in the family home. Pica was high in the absence of social environmental consequences, and no stimuli competed. Response interruption and redirection with differential reinforcement was effective in increasing independence in multiple contexts with 7 skills such as discarding, putting away, and engaging with some materials appropriately (apply sunblock, put and keep sun hats on, play with beach toys and a sand and water play table), and refraining from touching other items (e.g., mud puddle, other’s food). Toy engagement increased and pica decreased. He met 100% of goals and learned to drink potable water and eat appropriately from crockery on a table. Parents were trained and reported high social validity, and gains maintained.

Children with paediatric feeding disorders may not naturally develop typical chewing skills to eat age-appropriate food textures. There are only a handful of studies on teaching chewing, and even less for children without any chewing history. Additional research is needed on increasing food texture and chewing skills, particularly internationally in settings outside of intensive specialised interdisciplinary hospitals. A 5-year-old male with autism, iron deficiency, supplement deficiency, low weight, and history of constipation had never chewed or eaten regular texture food in his life, even baby rusks/puffs or mashed food. He was dependent on blended “baby” food and would not swallow any lumps or texture due to gagging and refusal. He would only eat certain blends/brands and regressed to drinking only milk if his food was unavailable. For most of his life (>4 years), parents consulted with a wide variety of professionals (e.g., paediatrician, headstart feeding specialist), and he had over a year of outpatient treatment and a week of inpatient hospitalisation treatment from an interdisciplinary feeding programme, and years of previous failed treatment attempts including speech, occupational, and behavioural therapy. If food entered his mouth, he would try to swallow before it was chewed, gag, spit out, etc. We used a modified multiple baseline probe across food textures design. After 3 weeks of solely behaviour-analytic treatment, “Junot” was eating (chewing and swallowing) a full plate of regular texture portions of a variety of 109 foods from all food groups. He learned to bite off, chew, lateralise, masticate, judge, and swallow a wide variety of regular texture foods, including some meats and raw fruit and vegetables. We trained his parents to implement the protocol with high integrity. He met all 100 % of goals. Parents reported high satisfaction and social acceptability and gains were maintained to 1-year follow-up.

A small but growing body of research in pediatric feeding disorders asserts the importance of comprehensively measuring social significance of goals, procedures, and effects of intervention, and incorporating social validity into practice to inform treatment. This report sought to extend this literature by detailing procedures to measure and improve social validity during a clinical case of a 3.5-year-old during a home-based intensive feeding program. A multiple baseline design demonstrated effectiveness of nonremoval and re-presentation added to a treatment package. Repeated choice via direct child preference assessments informed demand fading and gradual progression across six feeding skill domains (medication, cup drinking, independence, texture, volume, variety) and arrangements of response effort (preference, skill) with layers of reinforcer parameters (quality, magnitude, rate, immediacy). Indices of happiness definitions were modified, and extinction bursts examined. Fostering a collaborative approach, caregivers provided detailed input on social validity measures pretreatment, at discharge, and long-term follow-up (6-month, 1-year), inclusive of both qualitative and quantitative responses, written and verbal communication, and permanent product data. Further implications for practitioners included detailing the process for caregiver training and generalization to family meals with siblings and community settings, and providing adaptable full-text guidelines for free access/choice contexts.

Saliva packing can be one of the most severe life-threatening and challenging behaviours to treat. A 9-year-old male with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability had 100% nasogastric (NG) feeding tube dependence and significant adaptive behaviour regression (in speaking, using the toilet and his hands, school attendance, sleep). He participated in an intensive behaviour-analytic paediatric feeding treatment programme. Saliva packing, as an automatically-maintained undifferentiated behaviour that persisted in all waking contexts despite high engagement in activities, warranted an additional outside of meal approach. He began swallowing, met 100% of his 21 goals, gained weight, and eliminated tube dependence. He reached a variety of 94 across all food groups, drinks, and supplements. Caregivers were trained and reported high social validity, and gains generalised and maintained in 1-month follow-up. This is the first case to our awareness in Australia of an in-home solely behaviour-analytic intervention to eliminate tube dependence, and it was conducted without hunger provocation, weight loss, or limited nutritional variety.

Prolonged tube feeding has a multitude of negative outcomes. The transition to oral feeding is essential for child and family quality of life. Behaviour-analytic interventions are effective for paediatric feeding disorders, but information is lacking regarding the treatment process and outcomes. This study evaluated a home-based behavioural intervention for a 19-month-old child dependent on tube feeding. An intensive period was followed by caregiver support to advance feeding skills. We applied differential reinforcement and volume fading within a multiple probe design. Results showed clinically significant behavioural and nutritional outcomes, the cessation of tube feeding, and a process valued by the family. *Note: Conducted by Dr. Sarah Ann Taylor (Leadley) in New Zealand.

ARFID can occur in children with typical development and persist past childhood. This significantly impacts most areas of children’s lives, but may become more evident in teenage years, especially socially. There is an empirically supported treatment for ARFID with 40 years of research backing, this being behaviour-analytic feeding interventions. However, application to individuals over age 12 is lacking, and needs to be investigated for effectiveness. This is important as the addition of ARFID (formerly called feeding disorders) to the DSM-V has seen an increase in new treatments for ARFID by attempting to apply eating disorder treatments to this population including children. More research is needed to identify if already established behavioural intervention procedures are effective for ARFID in individuals with selectivity, without disabilities, older ages, and in settings outside of intensive specialised feeding hospital admissions in the United States. A 13-year-old female with ARFID and years of failed treatment attempts participated in her home in Australia. She consumed no vegetables or fruits. Her diet was limited to 5 specific starches, 1 protein, and 1 combo. She was motivated to change her diet because of social and health (never feeling full, low energy, spikes/crashes) impact. Socially, this posed a significant problem at school, with friends and family, and during occasions and travel. Previous treatment attempts since the age of 2 years included psychologists, eating disorders specialists, dietitians, speech/occupational therapists, gastroenterologist, anxiety medications (with side effects), hypnosis, sensory treatment (SOS), play therapy, rewards, removal of privileges, withholding food, etc. We conducted multiple stimulus without replacement preference assessments and used a changing criterion design with multiple baseline probes. Treatment consisted of demand fading, choice, differential attention, and contingent access. We did not use cognitive or family based treatment. Consumption increased to 100%. Variety reached 61 foods across all food groups. She met 100% of goals and ate at a restaurant. Caregivers reported high satisfaction and social acceptability. Gains were maintained at 9 months. This brief, behaviour-analytic in-home treatment was effective in increasing food group variety consumption.

Packing involves not swallowing solids or liquids in the mouth. It is a significant mealtime behaviour to treat. Research has shown effectiveness of redistribution, but only two studies in highly specialised hospital settings in the United States have evaluated the use of a chaser. We extended this literature by conducting treatment in the home setting, and comparing a liquid and puree chaser separately to infant gum brush redistribution and a move-on to the next bite presentation component. A 4-year-old male with autism spectrum disorder and gastrostomy tube dependence participated in his home. He also had a history of prematurity (24 weeks), ventilator, CPAP, oxygen, and failure to thrive. He ate custard and soup as a nonself-feeder at a certain temperature. If a minuscule lump was in the soup, he would gag and vomit. He had never chewed or used his teeth or swallowed any texture. He might accept 2 other specific foods, but would pack for hours or expel. He consumed chocolate milk mix via spoon feeding as a nonself-feeder. He used an adaptive water bottle that squirted water into his mouth with prompting and assistance. He did not take medications orally (via G-tube). Previous treatment attempts included multiple years since birth with a hospital feeding team, various therapies, and a 10-day hospitalisation for tube weaning (resulting in some small oral intake of custard, liquid soup, and chocolate milk mix). His parents persisted in oral feeding and volume and decreased tube nutrition dependence on their own. We used a multielement single-case experimental design. With the liquid chaser, consumption increased to 100%. Swallowing latency was significantly lower with the liquid chaser compared to other packing treatments. His variety reached over 124 foods at any temperature. He learned self-feeding and scooping, including holding the container, and using a fork. He learned drinking independently from a full cup including sipping, a regular water bottle, and regular straw. Liquid variety was increased to multiple flavours of formula and water in a regular open cup. He learned to eat independently from pouch and take medications orally rather than via tube. He learned to bite off, chew with his molars, lateralize, masticate, and swallow a wide variety of regular texture foods, including meats and raw fruit/vegetables. Refusal, expulsion, packing (not swallowing), emesis (vomit), and gagging/coughing all decreased to low/zero levels, and independence, chewing/texture, and swallowing increased significantly. He transitioned from a highchair to a booster at the family dinner table. His parents were trained to implement the protocol. He met all 22 of his goals in 15 days.

Use of an Exit Criterion for a Clinical Paediatric Feeding Case In-Home (Taylor, 2020)

There are well-established empirically-supported treatments for paediatric feeding disorders (avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder; ARFID); however, more research is needed on their sole use, outside of specialised multidisciplinary feeding hospitals, and with older ages. Additionally, there is little research on the use of an exit criterion treatment. An 11-year-old male with autism participated in a 2-week in-home programme. He ate no fruits or vegetables, rarely used utensils, did not drink out of a cup, and had constipation and laxative dependence. He engaged in inappropriate mealtime behaviour (IMB) if foods were near him (other’s eating), gagged at the smell, and requested his mum to wash her hands before touching his water bottle if she cut vegetables. Previous treatment attempts include 18 months with an OT from a multidisciplinary feeding team and speech therapy. Treatment was solely behaviour-analytic and consisted of demand fading, choice, differential attention, contingent access, and exit criterion. We conducted repeated edible preference assessments and used a changing criterion single-case experimental design across three food variety groups of decreasing preference. Variety reached 79 foods across food groups and 100% of goals were met (including utensils and cup drinking). He ate at a restaurant and with his sibling. Caregivers reported high social acceptability and at 2-year follow-up the problem still resolved.

Early childhood feeding problems can be challenging. Children who limit their food consumption may significantly impact multiple critical areas of development. Effective treatment should be accessed as early as possible but has been limited to a handful of US hospital programmes. Feeding problems affect both children with and without disability, and families may struggle with multiple children having feeding difficulties. We provided short-term (less than 2 weeks), in-home, intensive, behaviour-analytic feeding intervention to two children with typical development who were younger siblings of children already in the programme. A 2-year-old male ate 1 protein starch combo, 2 proteins (1 restaurant specific), 3 starches (1 restaurant specific), 1 fruit, 1 vegetable, and smoothies/milkshakes. A 2.5-year-old male consumed a few specific starches, specific homemade omelette, 1 fruit, and certain pureed/ground mixtures (if fed as a nonself-feeder with iPad). He expelled (spit out) foods, would not self-feed most foods, and did not consume foods from the food groups separately or at an age-appropriate texture. We used a withdrawal/reversal design to assess the effects of nonremoval of the spoon, re-presentation, contingent and noncontingent access to tangibles, differential attention, and response cost. This multi-component intervention was effective in increasing the consumption of a wide variety of foods at regular texture and self-feeding for both participants. Variety was increased to over 60 foods from all food groups. Admission goals were met (100%). We trained caregivers to high procedural integrity and generalised the protocol. We provided actual plate picture examples of family meals consumed where the brothers and parents ate the same meal. Caregiver satisfaction and social acceptability were high. Gains were maintained at 3-year follow-up where parents reported problems were fully resolved.

Research from specialised hospital feeding programmes in the United States has shown effectiveness of a variety of treatments for packing (not swallowing food or liquid in the mouth) to increase swallowing and consumption. One potential component used in clinical practice has not been evaluated in the literature to our knowledge. This component is move-on and involves moving on to the next bite presentation rather than waiting for swallowing (i.e., clean mouth). A 5-year-old female with autism spectrum disorder (level 3) and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder participated in a home setting in Australia for 2 weeks. She had constipation, low height/weight, mild eczema, dyspraxia, toothbrushing/medication refusal, recent history of formula dependence, and did not eat any vegetables. She primarily ate plain starches. She did not eat enough volume or drink enough water or at school. She overstuffed her mouth, packed, expelled, or had emesis (vomit). She received nearly 2 years of behavioural feeding treatment attempts and early intervention, speech, OT, and physiotherapy. We used a withdrawal/reversal single-case experimental design for a move-on component added to a treatment package. With move-on added, latency to clean mouth decreased and consumption increased to 100%. After the treatment evaluation, additional procedures (interspersal, redistribution) were needed in full plate and portion meals. Food variety was increased to 116 regular texture foods across all food groups. All (100%) of admission goals were met including independently drinking water and self-feeding. Parents were trained to high procedural integrity, and the protocol was generalised to the community in a family meal at a café. Gains maintained to 1-month follow-up.

Researchers have shown the effectiveness of physical guidance procedures in highly specialised hospital settings. We replicated use of a side deposit in a treatment package using a reversal design. We extended by translating to a home setting in Australia. We also evaluated the frequency and necessity of use over time to 13 months, choice and positive reinforcement alone prior, and food preferences before and after exposure. A 9-year-old boy with autism and history of nasogastric tube (NG tube) at birth ate no fruits, vegetables, or meat and did not drink water, and was dependent on laxatives and formula. He had years of attempted treatments with multiple disciplines and therapists, including medications and participation in an intensive research study at a hospital. Choice and contingent access, differential attention, nonremoval, and re-presentation were ineffective in increasing consumption, but it increased to 100% when the side deposit was added. Variety increased to 57 regular texture foods and water from a cup. He met 100% of goals. His parents reported high satisfaction and acceptability. Treatment gains maintained over a year in the absence of protocol implementation.

Assessment and Treatment of Pica Within the Home Setting in Australia (Taylor, 2020)

Pica is one of the most serious, life-threatening topographies of self-injurious behavior because a single instance can result in death. Despite this, there is a need for more research on teaching adaptive skills to replace pica, particularly outside of intensive specialized hospital admissions and with younger children. We present a case history of a 4-year-old male with autism spectrum disorder, pica, food selectivity, food stealing, and history of iron deficieny in which assessment and treatment occurred in the family’s home for 9 days. Pica was significantly impacting his life and restricting his location, daily activities, independence, and adaptive functioning. He could not go outside freely because he ate dirt, bark, grass, rocks, rubbish, etc. He also ate academic materials such as glue, crayons, plastic, paper, paint, etc. He mouthed and bit many dangerous household objects (e.g., extension cord, cleaning products) and toys which had visible teeth marks and bits missing. Food stealing impacted his daily life and social engagement, significant others, and community and social settings. Cupboards and outdoors were locked. He did not consume any vegetables separately and only ate 3 fruits. A functional analysis suggested pica was maintained by automatic reinforcement. A competing stimulus assessment showed pica was highest without competing stimuli, lowest with highly preferred edibles, and lower with highly preferred tangibles. Response interruption and redirection with differential reinforcement was effective with and without competing stimuli across contexts. The participant learned to independently throw away pica material and rubbish, put away objects he previously engaged in pica and mouthing with, and use appropriately some materials (academic, leisure, therapy), and to refrain from touching other items he previously consumed inappropriately (dangerous, inappropriate, or belonging to others such as food, electronics, and household items). Pica decreased by 97%, independent discards increased by 100%, and 100% of admission goals were met. He independently accepted, chewed, and swallowed 25 new foods including 12 vegetables and 8 fruits. His mother and therapist were trained to high procedural integrity on the treatment procedures, and they continued testing for generalization and maintenance. His mother reported high satisfaction with the program and outcomes and acceptability of the treatment procedures. Gains were maintained for over 2 years.

Side Deposit with Regular Texture Food for Clinical Cases In-Home (Taylor, 2020)

Research has shown effectiveness of nonremoval of the spoon and physical guidance in increasing consumption and decreasing inappropriate mealtime behavior. The side deposit has been used to treat passive refusal in 2 studies (1 in a highly specialized hospital setting) using lower manipulated-texture foods on an infant gum brush. We extended the literature by using regular texture bites of food with a finger prompt and side deposit (placing bites inside the side of the child’s mouth via the cheek) in an intensive (2-3 week) home-based program setting in Australia, demonstrating that attention and tangible treatments alone were ineffective prior, fading the tangible treatment, showing caregiver training, and following up. 2 male children with autism spectrum disorder (with texture/variety selectivity; one with liquid dependence) participated in their homes. A 5-year-old boy with autism consumed 4 specific foods and no fruits or raw or separate vegetables or age-appropriate texture foods. A 4-year-old male with autism, medication refusal, and iron deficiency with supplement dependency was dependent on liquids and formula to meet his nutritional needs via baby bottle. He did not eat any foods, only specific biscuits and a homemade fruit smoothie as a nonself-feeder. He did not drink out of an open cup. He would not eat from his school lunchbox if a nonpreferred food was included. He had had over 2 years of failed treatment attempts from multiple disciplines. We used a reversal design to replicate effectiveness of the side deposit added to a treatment package. For both participants, we observed a >98% decrease in latency to acceptance, a 100% decrease in inappropriate mealtime behavior, and a 100% increase in consumption with the side deposit added. Variety was increased to over 85 regular texture foods including steak and salad. 100% of admission goals were met including independently scooping and biting off, chewing regular texture, self-drinking from open cup, taking medication from a medicine cup, and transitioning independently to the table. Caregivers were trained to high procedural integrity and the protocol was generalized to school and the community (restaurant). Gains maintained to 3 and 1.5 years. This is important work in adding to the literature and support for the side deposit and expanding to regular texture, as well as replicating and extending empirically supported treatments for feeding internationally to the home setting.

Redistribution for Regular Texture Bites for Clinical Pediatric Feeding Cases In-Home (Taylor, 2022)

Research has shown effectiveness of redistribution procedures for decreasing packing and increasing swallowing. Redistribution has been done using lower manipulated-texture foods on an infant gum brush in specialized U.S. hospitals. We extended this by using regular texture bites of food in a short-term (1–2 weeks) home-based program in Australia, showing decreased then absent use of the procedure, and following up. Two children with autism spectrum disorder participated. A 5-year-old male with autism (level 3), constipation, laxative/supplement dependency, lactose intolerance, toothbrushing refusal, and history of reflux in infancy ate 1 specific cracker and thin hot chips. He was not eating any foods that required chewing or utensils for feeding skills. He did not scoop and flipped his spoon (food fell off). He did not eat away from home or during mealtimes (grazed). He had feeding treatment attempts for years including ST, OT, and behavioural and sensory-based therapies and “desensitisation.” He had early behavioural intervention. He was taught to pack food on his tongue resulting in gagging and vomiting and not chewing or moving food to his teeth. He had problem behaviour and was on psychotropics. A 4-year, 3-month old female with autism (level 2) did not eat any vegetables or fruits, drank from a baby bottle, and had never chewed regular texture foods. She expelled (spit out) food, gagged, overstuffed her mouth, engaged in refusal, and did not eat at childcare or when travelling. She required the iPad and large dessert rewards to eat. She ate only 3 combinations foods. She had tooth decay, sleep problems, problem behaviour upon denial of preferred foods, medication refusal, constipation, and was not toilet trained for bowel movements. We used a modified withdrawal/reversal design. Latency to swallow decreased. Participants increased variety to 90 and 122 regular texture foods across food groups. All goals were met including increasing independence in self-feeding, using a fork, regular texture. Both parents were trained and she ate at a restaurant. Gains maintained to 6 months and redistribution was no longer needed.

Behavior analysts typically rely on visual inspection of single-case experimental designs to make treatment decisions. However, visual inspection is subjective, which has led to the development of supplemental objective methods such as the conservative dual-criteria method. To replicate and extend a study conducted by Wolfe et al. (2018) on the topic, we examined agreement between the visual inspection of five raters, the conservative dual-criteria method, and a machine-learning algorithm (i.e., the support vector classifier) on 198 AB graphs extracted from clinical data. The results indicated that average agreement between the 3 methods was generally consistent. Mean interrater agreement was 84%, whereas raters agreed with the conservative dual-criteria method and the support vector classifier on 84% and 85% of graphs, respectively. Our results indicate that both objective methods produce results consistent with visual inspection, which may support their future use.

Practitioners in pediatric feeding programs often rely on single-case experimental designs and visual inspection to make treatment decisions (e.g., whether to change or keep a treatment in place). However, researchers have shown that this practice remains subjective, and there is no consensus yet on the best approach to support visual inspection results. To address this issue, we present the first application of a pediatric feeding treatment evaluation using machine learning to analyze treatment effects. A 5-year-old male with autism spectrum disorder (level 2) participated in a 2-week home-based, behavior-analytic treatment program. He had severe constipation, laxative dependence, recent history of baby bottle and current formula dependence, liquid refusal, medication refusal, viral asthma, and eczema, and did not eat any fruit or vegetables. He ate only 2 proteins and 5 starches and 1 combo. He did not drink enough fluid or eat enough volume consistently, drink at school, or sit at the table for meals. He had impactions and bowel stretching with decreased sensation that impacted toilet training attempts and had physiotherapy. He had therapy attempts since 18 months of age (ST, OT, multidisciplinary autism feeding team, behavioural therapy/psychology, sensory book, wide variety of approaches and strategies, multiple programs in an autism specific program). His variety increased to 67 foods from all food groups. He increased his liquid volume and eliminated formula dependence. He ate with his parents and sister. His parents were trained to implement the protocol with high integrity. He met all (100%) 9 of his goals and maintained at 1-year follow-up. We compared interrater agreement between machine learning and expert visual analysts on the effects of a pediatric feeding treatment within a modified reversal design. Both the visual analyst and the machine learning model generally agreed about the effectiveness of the treatment while overall agreement remained high. Overall, the results suggest that machine learning may provide additional support for the analysis of single-case experimental designs implemented in pediatric feeding treatment evaluations.