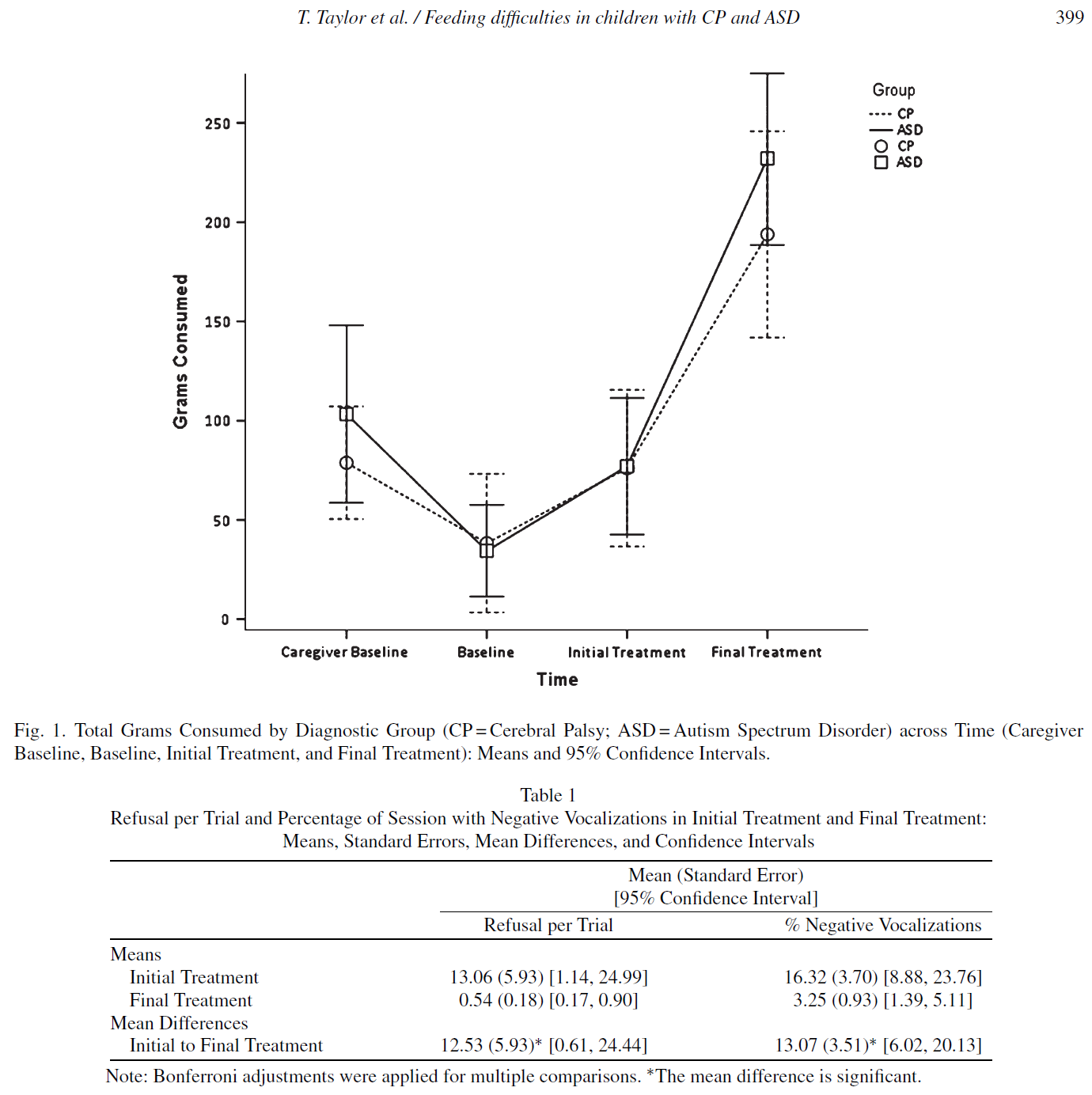

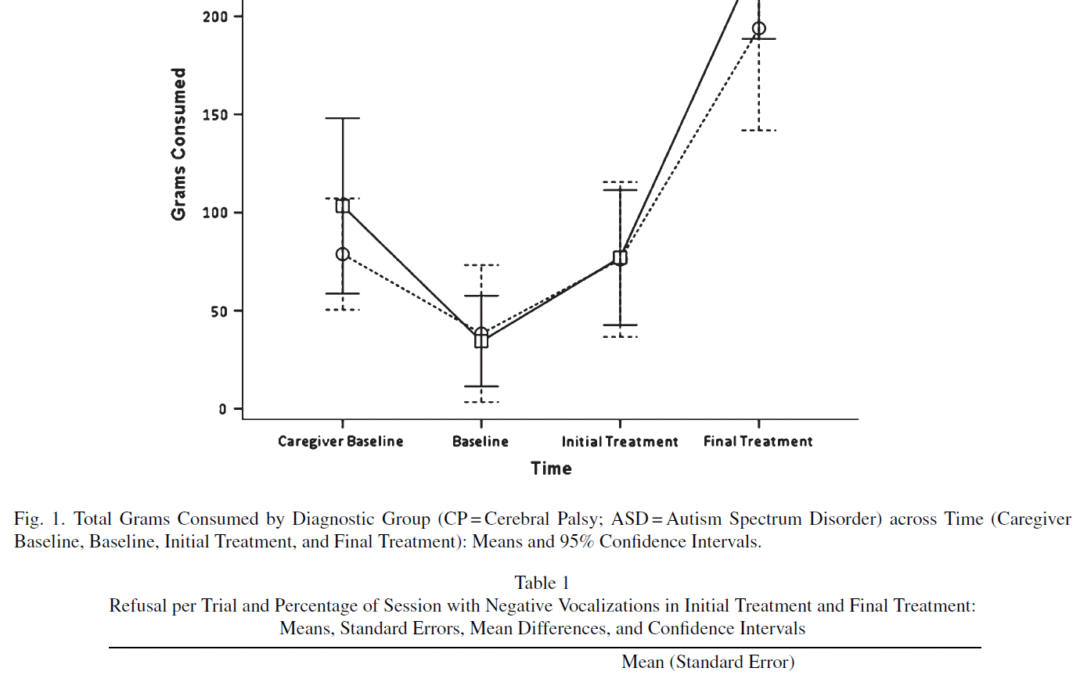

The reason we published this article is that a good thing about empirically-supported treatments for feeding difficulties is that they work regardless of the original cause, diagnosis, disability level, or tube status. Unfortunately, parents may be inappropriately told things like: their child couldn’t eat (or would never self-feed or chew, etc.; with a lack of assessment or treatment data to support this), ABA (applied behavior analysis; behavior-analytic treatment) is only for autism, for cerebral palsy (CP) they should automatically go to speech and OT (occupational therapy) instead, or ABA is for decreasing inappropriate mealtime behavior rather than teaching skills. Caregivers have reported thinking their child was not able to do treatment and asking if they are able to do the feeding program if they don’t talk or understand instructions; However, this treatment is tailored to each child’s level and needs and still works, and actually in the hospital we mostly saw toddlers (younger) with more developmental disabilities and medical problems. The thought should not really be ‘if’ they can learn it, but ‘when’ or what it will take. It may just take more time, especially to teach chewing and reach regular texture and full meal volumes, although still we’re just talking about weeks/months—not years.

So, when may this treatment not be appropriate or enough? Here are some examples: if there are body image concerns (ie, eating rather than feeding disorders), if the child is NPO due to aspiration (medical team said child is unsafe to swallow as food or liquids may go into their lungs ie, ‘going down the wrong pipe’), uncontrolled seizures or pain, TPN (total parenteral nutrition; IV is going into veins instead of stomach). Some people may need a highly controlled expert hospital setting like KKI (Kennedy Krieger Institute) where this article was published if they are older in age or have aggression, self-injury, pica, rumination, etc. and more resources are needed.