There have been recent reports of teenagers becoming blind due to poor diets as well as the return of conditions like scurvy in developed countries. There has also been an increase in attention with the addition of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID; aka feeding disorders) to the DSM-V. However, this is not a new disorder and there is already a well-established empirically supported treatment for it that has decades of research backing. This new article shows this solely behavior-analytic treatment working for a 13-year-old in a home setting.

“Haydell” was 13-years-old and didn’t have any diagnoses or developmental disabilities. Feeding was having a huge impact on her socially going into her teenage years so she was self-motivated to improve her diet. She could communicate the negative impacts of this to us, which was novel and interesting as much of our area is with younger kids with developmental disabilities. Since she was 2, for years she had heaps of previous failed treatment attempts (eg, hypnosis, meds, all disciplines). As a toddler, this would have been a typical pediatric feeding disorder presentation.

With a simple behavioral treatment with no cognitive or talking therapy, she got to 61 foods in less than 2 weeks. She did it all herself and didn’t need any prompting. We had her graduation meal at a restaurant with cuisine from an overseas country she wanted to travel to (and ate many new foods–we were super impressed!), which she later did!

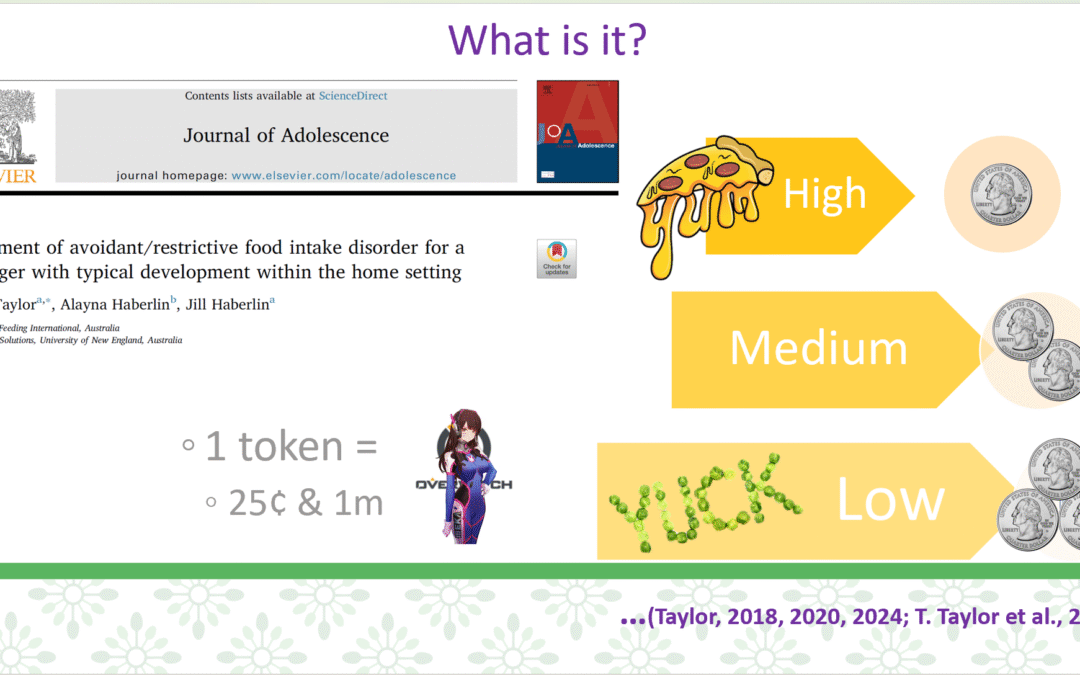

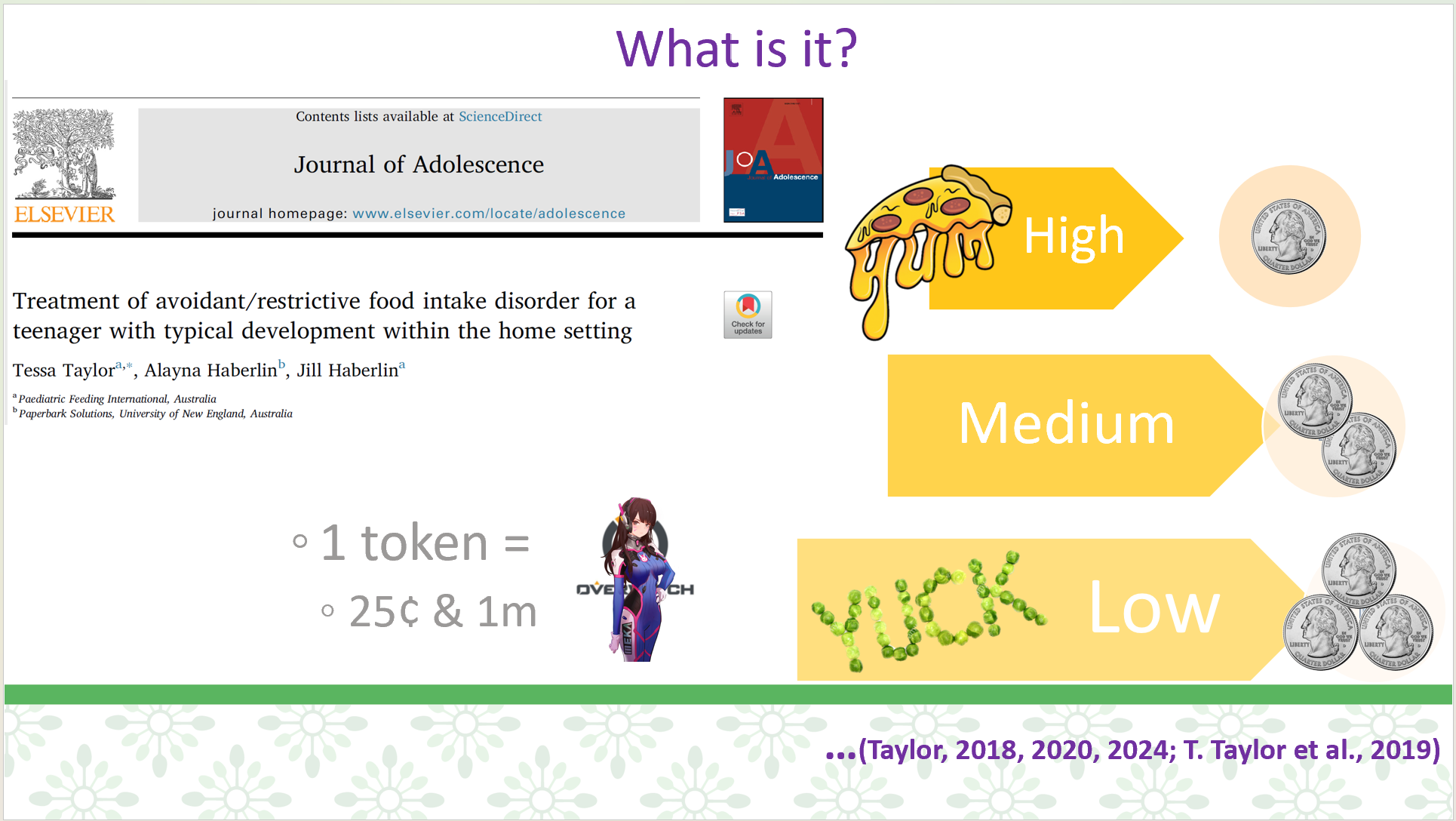

She helped develop the plan and made lots of choices. She wanted to tackle hard foods like plain raw vegetables without dips, etc. She made repeated choices of foods, and got different earnings for levels of foods as her preferences changed over time due to exposure, so more tokens for harder/less preferred foods. We did repeated preference assessments, made food groupings of variations or raw veg, 7 foods in each group, and graphed how her preferences changed over time due to exposure (practicing eating them). We removed the foods she ate and matched foods to tokens earned so she earned more for increasingly harder foods. See the graphs below of a changing criterion design with demand fading and choice.

I was really nervous and cautious about taking this case. During intake, we made sure there were no symptoms of anorexia or bulimia particularly body image concerns. There also weren’t any family concerns—they had a good relationship and the parents ate a variety of foods including raw vegetables. I was very open with the family that this was not something I had done before, that it would be very simple practice and exposure, and she would have to actually eat the foods (the target/goal) and we wouldn’t be talking about it (like whether she liked it, it’s good for you, why don’t you want to eat it, etc.). We talked about even though she’s motivated, if she decided not to actually eat the food in action we wouldn’t make progress in consumption (people may say they want to, but either won’t in the moment or are saying it to please others, etc.). She seemed very mature and willingly talked to me and participated in the intake and planning. We talked in detail before beginning. For example, what was she most apprehensive about (eg, vomiting), turns out she was most worried she would fail and it wouldn’t work, but she smashed it and did amazing!

ABSTRACT

Introduction

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) can occur in children with typical development and persist past childhood. This significantly impacts most areas of children’s lives, but may become more evident in teenage years, especially socially. There is an empirically supported treatment for ARFID with 40 years of research backing, this being behaviour-analytic feeding interventions. However, application to individuals over age 12 is lacking, and needs to be investigated for effectiveness. This is important as the addition of ARFID (formerly called feeding disorders) to the DSM-V has seen an increase in new treatments for ARFID by attempting to apply eating disorder treatments to this population including children. More research is needed to identify if already established behavioral intervention procedures are effective for ARFID in individuals with selectivity, without disabilities, older ages, and in settings outside of intensive specialized feeding hospital admissions in the United States.

Method

A 13-year-old female with ARFID and years of failed treatment attempts participated in her home in Australia. We conducted multiple stimulus without replacement preference assessments and used a changing criterion design with multiple baseline probes. Treatment consisted of demand fading, choice, differential attention, and contingent access. We did not use cognitive or family based treatment.

Results

Consumption increased to 100%. Variety reached 61 foods across all food groups. She met 100% of goals and ate at a restaurant. Caregivers reported high satisfaction and social acceptability. Gains were maintained at 9 months.

Conclusion

This brief, behavior-analytic in-home treatment was effective in increasing food group variety consumption.

“Haydell” was a 13-year-old girl with typical development and growth consumed no vegetables or fruits. Her diet was limited to 5 specific starches, 1 protein, 1 protein starch combo, and snack foods. She was motivated to change her diet because of social and health (never feeling full, low energy, spikes/crashes) impact. Socially, this posed a significant problem at school, with friends and family, during parties and events, at restaurants, and during travel. Previous treatment attempts since the age of 2 years included multiple consultations with psychologists, eating disorders specialists, dietitians, speech/occupational therapists, gastroenterologist, and anxiety medications, hypnosis, sensory treatment (SOS), play therapy, rewards, removal of privileges, withholding food, etc. Side effects of medication included carb cravings, weight gain, and lethargy. On the first day of treatment, she consumed 13 new foods at regular texture 100% independently including 6 raw plain vegetables. Variety reached 48 foods and she quickly met 100% of goals. She ate multiple new foods at restaurants and ate family dinners independently with no inappropriate mealtime behaviour. Caregivers reported high satisfaction (4.82/5) and social acceptability of the treatment (4.88/5). At 9-month follow-up, she no longer had ‘anxiety’ around food, and she still consumed at least 46 of the foods introduced. Some of the foods not being consumed was due to the family not cooking them or having them available rather than refusal. She was eating the family dinner including a raw salad daily and also was eating at school, at restaurants, and while traveling.

Want to learn more about ARFID vs eating/feeding disorders?

On diagnosis, one factor that is important to inform treatment is if the person has body image concerns (ie, eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia). I was surprised reading the new ARFID articles coming out that people (especially children and those with disabilities) were ending up in eating disorders hospitalizations (given feeding tubes, psychiatric drugs, and talking therapy) instead of getting empirically-supported treatment (EST). Eating disorders hospitalizations can be overly complex, restrictive, costly, and ineffective. Researchers are also missing the pediatric feeding disorders literature and instead trying to adapt older eating disorders treatments to this population rather than adding acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) to EST.